111. Liskov substitution principle#

Imagine that you have a class called Square and another called Rectangle. Which is the subtype and which is the supertype?

In mathematics, a square is a special type of rectangle so it might seem reasonable to let Square be a subclass that inherits from Rectangle.

However, in object oriented programming, this might lead to very unexpected behavior.

This is the famous ‘Circle-ellipse problem’, also known as the ‘Square-rectangle problem’.

Fig. 111.1 While a square is a rectangle in mathematics, translating this relationship directly into object oriented programming can lead to unexpected behavior. This is known as the ‘Circle-ellipse problem’ or ‘Square-rectangle problem’.#

The purpose of the, so called, Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) is to help us avoid creating type hierarchies that don’t make any sense.

Like Square inheriting from Rectangle.

Because such hierarchies are likely to lead to bugs.

The principle ensures that our subtypes truly extend the functionality of our supertypes without breaking any implied ‘contracts’.

Key point

The Liskov substitution principle ensures that an instance of a subclass can be used wherever an instance of its superclass is expected, without affecting the correctness of the program.

The Circle-ellipse problem#

Let’s dive deeper into the Square-rectangle problem.

Imagine a Rectangle class with two settable properties called Width and Height.

class Rectangle

{

public virtual int Width { get; set; } = 1;

public virtual int Height { get; set; } = 1;

}

Suppose that the class Square inherits from Rectangle without overriding any of its members.

We will then be able to change the width of a Square instance without simultaneously changing its height. Which means that we will end up with Square instances that aren’t squares.

class Square : Rectangle

{

// No overrides.

}

// This square does not behave like a square.

Square square = new Square();

// Expecting this to change both width and height.

square.Width = 10;

// Expecting 10 x 10.

Console.WriteLine($"{square.Width} x {square.Height}");

10 x 1

What if Square overrides these properties and redefines the behavior so that both methods change width and height at the same time?

Then we won’t end up with instances of Square that aren’t squares, but we’ve instead violated the contract of Rectangle.

class Square : Rectangle

{

int width, height;

public override int Width

{

get => width;

set { width=value; height=value; }

}

public override int Height

{

get => height;

set { height=value; width=value; }

}

}

Hint

When we upcast an instance of a subtype (like Circle) to a supertype (like Ellipse) then the compile-time type will be the supertype. At that point we expect the object to behave in accordance with the ‘contract’ of the supertype, and will be utterly surprised if it doesn’t.

Remember, since Square is a subtype of Rectangle it should be possible to use it wherever a Rectangle is expected and it should behave like one.

// This rectangle doesn't behave like a rectangle.

Rectangle rect = new Square();

// Expecting the properties to be independent.

rect.Width = 10;

rect.Height = 2;

// Expecting 10 x 2.

Console.WriteLine($"{rect.Width} x {rect.Height}");

2 x 2

So, what’s the takeaway?

Well, if we want to keep the properties Width and Height, then there cannot be a subtyping relation

Definition#

The Liskov Substitution Principle is a notion of ‘behavioral subtyping’ first introduced by Liskov in an influential keynote address and later refined in a paper by Barbara Liskov and Jeanette Wing. In essence, the principle states that objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of a subclass without affecting the correctness of the program.

Formal definition: Let \(P(x)\) be a property provable about objects \(x\) of type \(T\). Then \(P(x)\) should be true for objects \(y\) of type \(S\) where \(S\) is a subtype of \(T\).

The principle stipulates some type rules and some behavioral rules. All or some of the type rules are usually implemented by compilers while the behavioral rules have to be respected by developers.

Robustness principle#

The ‘Robustness Principle’ (also known as ‘Postels law’) was originally formulated for the specification of TCP but serves as a great mnemonic for both the type and behavioral rules of the Liskov substitution principle as well as type-safe variance.

Be conservative in what you do, be liberal in what you accept from others.

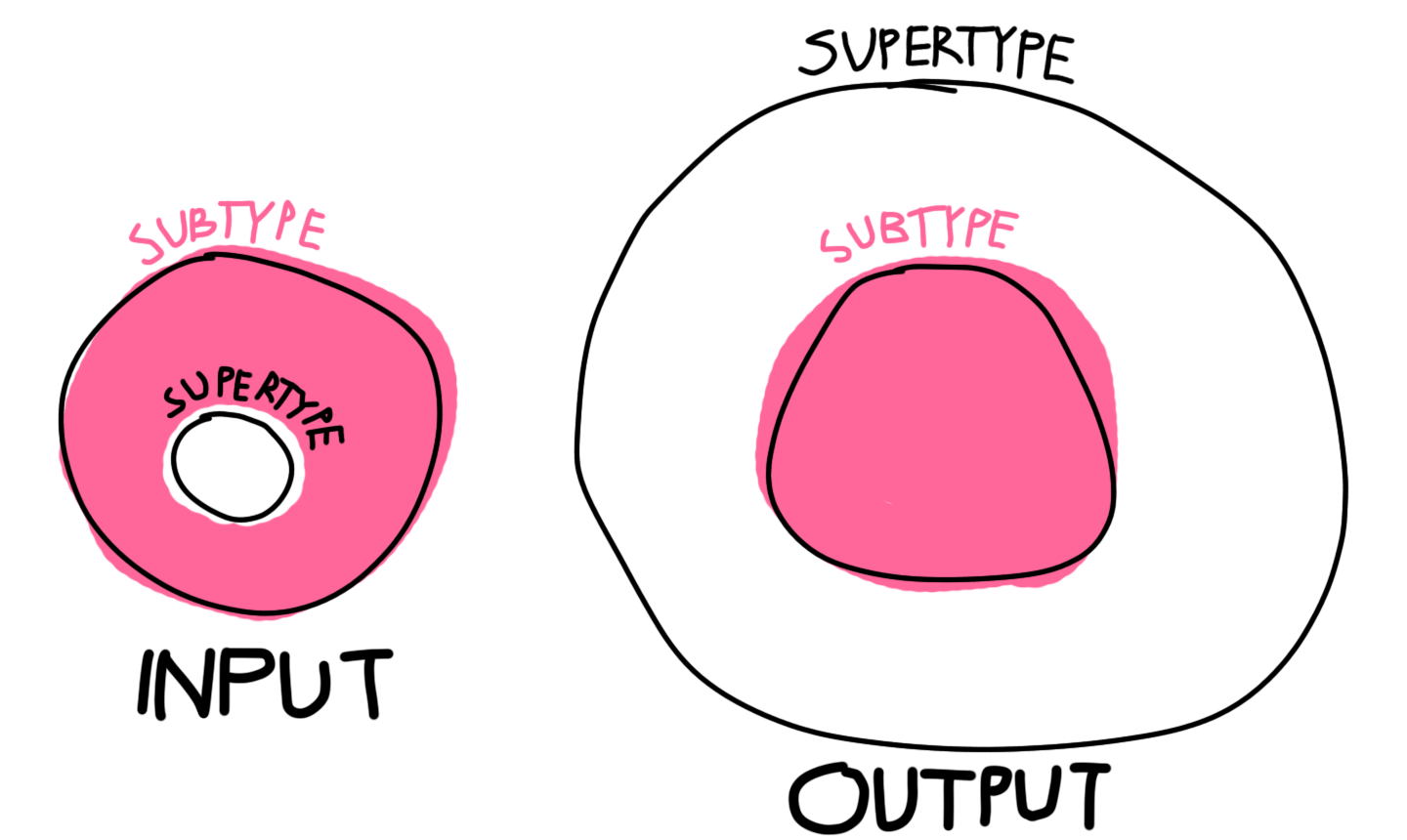

Essentially, it recommends that subtypes should be contravariant in their input parameters - meaning they should accept the same or broader types of data than their supertypes - and covariant in their output - restricting themselves to output types that are the same or more specific than those of their supertypes.

Tip

A subtype needs to be able to accept any value that the supertype can accept. Conversely, a subtype must only produces values that the supertype could produce.

Let’s think of this in terms of set theory and the visualization in Fig. 111.2. The set of possible values that a method in the subtype should be able to accept must be the same as or a superset of the set of input that the method in the supertype can accept. Conversely, the set of possible values that a method in the subtype should be allowed to return must be the same or a subset of the set of output values that the method in the supertype can return.

Fig. 111.2 The set of input that the subtype can accept should be the same or a superset of the input that the super The set of output that the subtype produces should be the same or a subset of the output that the supertype produces.#

Type rules#

To follow the Liskov substitution principle we must adhere to the follow three type rules:

Subtype method parameter must be contravariant.

Subtype method return types must be covariant.

Subtype exceptions must all be the same type or subtypes of exceptions in the supertype.

In line with the Robustness Principle, contravariant method parameters dictate that subtypes should accept the same or more general input types as their supertypes, ensuring no unexpected rejections.

Similarly, covariant method return types require subtypes to have the same or more specialized output types as their supertypes, preventing any surprises for users familiar only with the supertype.

The “no new exceptions” rule stipulates that any exceptions thrown by the subtype should be the same type or a subtype of those thrown by the supertype, again avoiding unexpected behavior for users.

Behavioral rules#

The Liskov substitution principle stipulates the following four behavioral rules:

Preconditions must be the same or weaker in the subtype.

Postconditions must be the same or stronger in the subtype.

Single-state invariants must be the same in subtype.

Multi-state invariants must be the same in subtype (this is also known as the ‘history rule’).

These rules hinge on three types of ‘predicates’ used in formal program specification: preconditions, postconditions, and invariants. Predicates are logical statements that can be either true or false.

Preconditions are the predicates that must be satisfied before executing a method. For example, a method requiring a positive integer input will throw an exception if given a negative one.

Postconditions are predicates that must be true after a method’s execution to validate its implementation.

For example a function returning the absolute value of a number must never produce a negative number.

In the Square-rectangle problem we violated the postconditions of the property Width when the subclass Square changed both Width and Height.

Single-state invariants are predicates that must constantly hold true within a type, like an instance variable staying within certain limits.

Multi-state invariants are predicates that need to be true across various states. This could mean, for instance, that a value must either stay the same or increase, but never decrease.

See also

Some languages have native support, so called, ‘formal specification’ which is concerned with preconditions, postconditions and invariants. Other languages, such as C#, have extensions such as Spec# that provide more compile-time and run-time support for verifying such predicates. All this allows us to express the behavioral rules of the Liskov substitution principle in code. However, principle doesn’t mandate the use of such tools, it merely employs formal terminology to clarify the meaning of substitutability.

See also

To learn more about how behavioral rules could be implemented by compilers I recommend that you read more about Design By Contract and Dependent Types.

Violations of Liskov substitution principle in .NET#

We discussed the widely used generic interface ICollection<T> in the chapter on collections.

There’s tons of collections like lists, sets, and dictionaries.

One method in the interface is Add, which is designed to add items to the collection.

In .NET there’s a class called ReadOnlyCollection<T>.

This class can’t possible support Add since its very idea is to be read-only.

Right?

Well, turns out that it actually implements ICollection<T>. 🤯

Now, is this a violation of the Liskov substitution principle?

Actually, it’s not.

Why?

Well, if this was the whole truth then it would have been.

But in the documentation of ICollection<T> it says that the Add method may throw a NotSupportedException if the collection in question does not support adding. 😤

So, ReadOnlyCollection<T> is not actually violating the ‘contract’ of ICollection<T> because the documentation of Add in ICollection<T> may throw an exception, which this particular implementation happens to do.

Although it’s not strictly a violation, this design weakens the interface’s usefulness. The whole point of compile-time type-checking is to discover errors at compile-time instead of at run-time. So, an interface whose methods might throw exceptions is significantly less useful than one whose methods don’t.

Also, from the perspective of a programmer who fails to discover this detail in the manual, this looks and behaves like a violation of the Liskov substitution principle. This is a completely unnecessary mess.

The motive might have been pragmatism. Perhaps to make collection-related features like LINQ work for read-only collections as well. But doing the wrong thing and calling it pragmatism is a slippery slope.

Note

There’s also IReadOnlyCollection<T> that appropriately doesn’t subtype ICollection<T>, making the decision for ReadOnlyCollection<T> to implement ICollection<T> seem even more questionable.

Conclusion#

The Liskov substitution principle isn’t just theoretical but has practical implications. Violating it leads to unintuitive type hierarchies which can cause unexpected bugs that are difficult to trace and fix, resulting in software that’s hard to maintain and extend.

The core tenet is simple but powerful: a subclass should be able to stand in for its superclass without altering the correctness of the program.

Rule of thumb

In the subtype, input can be liberal, output must be conservative, invariants must hold, and no new exceptions must be introduced.

So the next time you’re about to create a subtype, pause for a moment and ask yourself whether it truly adheres to the Liskov substitution principle. Your future self, and teammates will thank you for it.